Elizabeth Missing Sewell was born on Newport High Street on the 19th February 1815. ‘Missing’, a rather odd choice in middle name, is said to have been her godmother’s surname.

Elizabeth had eight brothers and three sisters, all of whom were fortunate enough to be granted an education. Their father held a range of positions, all of which were well paid. The Sewells also had two holiday destinations of choice on the Island; a rustic cottage on St Catherine’s Down called the Hermitage, and a parsonage in Binstead where an uncle named Edward resided.

The latter held a particular significance to the young girls because it contained a ‘choice little library’. The majority of the books it contained were considered unsuitable for women and for children, and so the little Sewells were not to touch them without express permission. Still, they were enchanted by it.

Elizabeth and her older sister, Ellen, were sent to a boarding school in Bath when they were aged 13 and 15. However, their time there was cut short when they were asked to return home and handle the education of their younger sisters, Janetta and Emma – possibly due to Janetta’s weak immune system.

Elizabeth wrote in her autobiography that her ‘whole heart was bent ... upon teaching Emma and Janetta, and making them happy.’ Ellen used her new-found leisure time to attend parties and other social events, while Elizabeth continued to study under her own terms. Even so, the two eldest Sewell sisters remained close as could be.

By the late 1840s, the siblings were living with an aunt following the deaths of both parents, and Ellen and Elizabeth had taken up charity work within their local parish. Bonchurch’s church, originally built during the Saxon era, was far too small for the size of its current congregation, and there was no local school.

Elizabeth was by this time writing and selling stories, all with a moral, Christian twist. When St Boniface’s Church was completed in 1848, £10 worth of its furnishings (around £800 in today’s money) were purchased with the profits from four of Elizabeth’s short stories.

Her next project was to build a school, as the only education available for children in Bonchurch was a Sunday school run by a woman named Rosa White in her home. Elizabeth did this with her sister, who was an artist. Ellen drew six sketches and Elizabeth, along with five friends, wrote stories to accompany them. The proceeds from the sales of this anthology, entitled The Sketches, then went towards building the new school. A.C. Swinburne’s father generously donated the remainder of the money needed for the project, although Elizabeth did later state that she thought they had managed to raise about £200 (around £16,000 today).

Bonchurch National School (so named because it was endorsed by the Church of England’s National Society for Promoting Religious Education) opened in the late 1840s/early 1850s. This school would likely have been aimed at educating the poorer children of Bonchurch, who were cut off from the facilities available in more populated areas of the Island during this time.

As well as helping to fund the education of the local children, Elizabeth and Ellen began to take a small group of children into their family home for lessons. They started with six local girls, including their own nieces (their brother had been recently widowed), and grew from there – seven was the standard number, although this could vary slightly. Defying traditional views on the education of girls, Elizabeth encouraged her pupils to read widely, and to question the world around them.

The sisters always viewed their enterprise as a ‘family home’ more than as a strict school environment. By 1866, Elizabeth was convinced that the middle-class girls of Ventnor (and the surrounding areas) needed a better source of education, too. She founded St Boniface School, which came to be known later as St Boniface Diocesan School.

Exclusively for girls, St Boniface was run by Elizabeth, Emma, and Ellen, with a few sought-after places for well-to-do girls, some travelling across oceans even to be granted this privilege – Elizabeth Chanler, for example, was sent by her father from America. Word seems to have travelled, largely due to Elizabeth Sewell’s successes as a writer. Her first novel, Amy Herbert, proved popular in the United States as well as at home in the UK.

The school building still exists today, and while it is no longer used as an educational facility, a plaque on the front of the building does commemorate its original purpose.

After the death of her sister in 1897, Elizabeth’s mental health began to decline and she fell into a deep depression. She outlived all of her siblings, Ellen passing in 1905, although their children – her nieces and nephews, as well as all the pupils she’d helped access an education over the years, provided for and took care of her until her death in August 1906.

There is a memorial plaque for Elizabeth, Ellen, and Emma in St Boniface Church in Bonchurch, as well as a prayer desk ‘given by friends in gratitude for her life and teaching’ in 1911.

In a time when educating women formally was a controversial matter, the Sewell sisters went above and beyond to ensure that the girls in their community were given chances they were not receiving elsewhere – either on the Island, or in the UK as a whole.

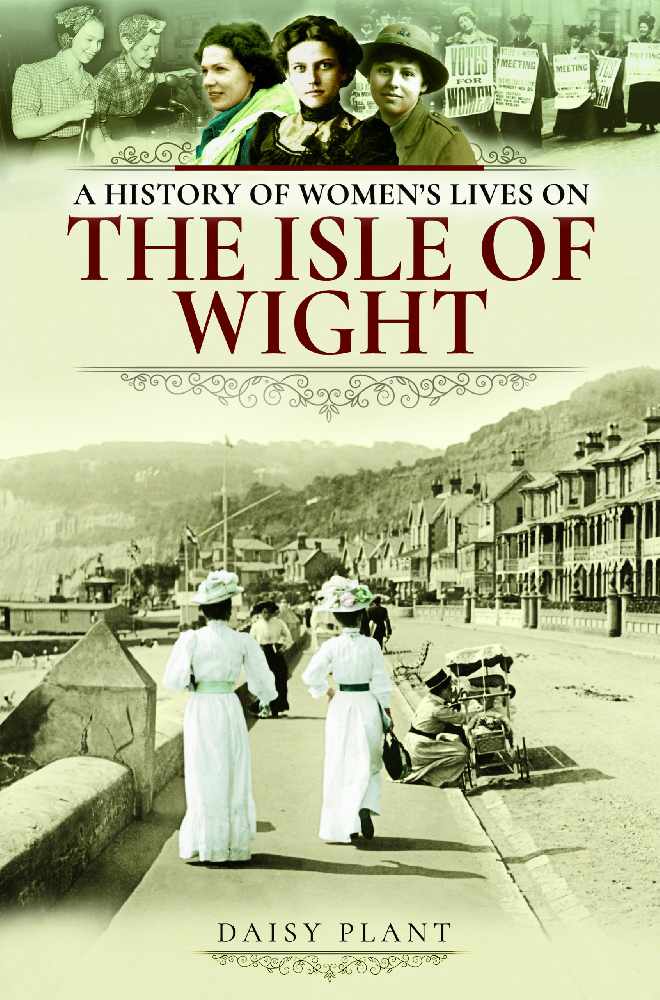

Read more about the history of women's lives on the Isle of Wight, in this fantastic book by Daisy Plant. Available from Medina Books in Cowes High Street. Also online at www.pen-and-sword.co.uk or by calling 01226 734222.

Island Update: January 2025

Island Update: January 2025

Ryde Rotary Centenary: 100 Years Strong

Ryde Rotary Centenary: 100 Years Strong

Home Style: Scandi Island Life

Home Style: Scandi Island Life

What to Watch in January 2025

What to Watch in January 2025

Entertainment Guide: January 2025

Entertainment Guide: January 2025

Memorial Held Following Death Of Kezi's Kindness Founder Nikki Flux-Edmonds

Memorial Held Following Death Of Kezi's Kindness Founder Nikki Flux-Edmonds

Mountbatten Inviting Islanders To Sign Up For 2026 Lapland Husky Trail

Mountbatten Inviting Islanders To Sign Up For 2026 Lapland Husky Trail

Home Style: Winter Wonderland

Home Style: Winter Wonderland

Help Available For Islanders To Cut Energy Bills

Help Available For Islanders To Cut Energy Bills

Island Update: December 2024

Island Update: December 2024

New Home For Citizens Advice Isle Of Wight

New Home For Citizens Advice Isle Of Wight

The Alternative Guide to Christmas Gifts

The Alternative Guide to Christmas Gifts

Island Family Launches Appeal For Teenage Son With Brain Tumour

Island Family Launches Appeal For Teenage Son With Brain Tumour

What to Watch in December 2024

What to Watch in December 2024

A Gardener’s Best Friend: The Story of Bob the Robin

A Gardener’s Best Friend: The Story of Bob the Robin

Memorial Quilt To Be Displayed On The Island

Memorial Quilt To Be Displayed On The Island

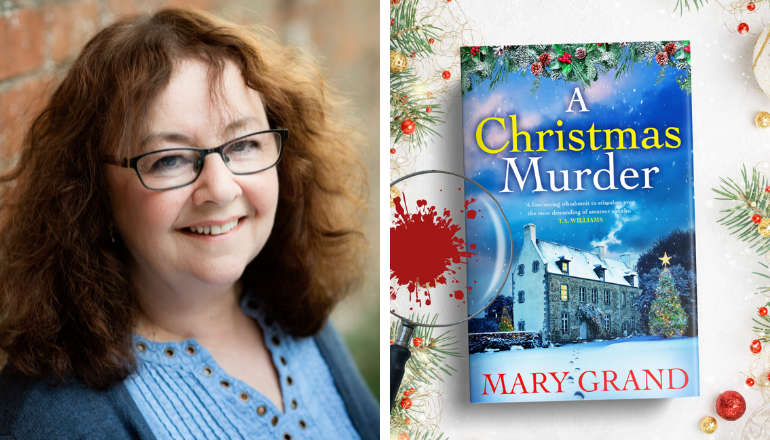

Island Author Celebrating Amazon Number One

Island Author Celebrating Amazon Number One

Amazing Isle Of Wight: Listener Photo Gallery

Amazing Isle Of Wight: Listener Photo Gallery

Falcons Fly Again At Robin Hill

Falcons Fly Again At Robin Hill

Island Update: November 2024

Island Update: November 2024